Are weight loss jabs a worldwide fix?

Published: 31 March 2023

By: Louise Zacest

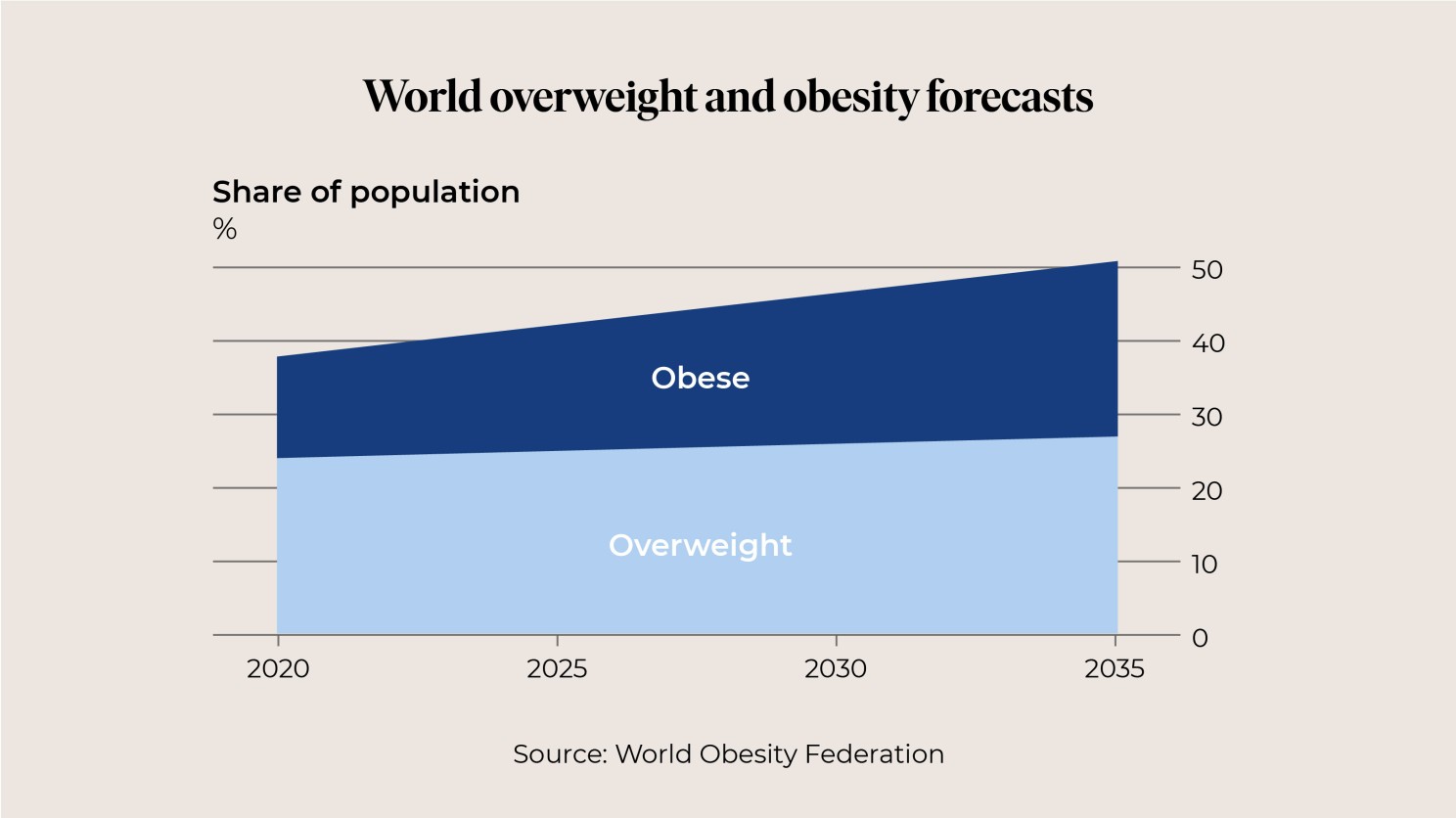

Despite the world shelling out $250 billion on weight loss products and services annually, two fifths of humanity are overweight or obese. That’s 3.2 billion of us who are not as healthy as we could be, and by 2035, this could increase to 4 billion humans, according to the World Obesity Federation. It’s not as if it’s just a first-world problem. Developing countries are all experiencing this alarming trend.

We’re getting fatter, and so far, no amount of jogging, aerobics, jazzercize, Keto, Atkins, Paleo, or ‘healthy’ carb diets have been able to hold back the planet’s growing waistlines. This rise in obesity isn’t merely a sign of poor discipline or willpower. In fact, the issue starts at a biological level. Humanity’s genes evolved to help our bodies maintain extra fat over winter or during famines, and they’re still fulfilling their cellular instincts to resist losing weight.

This biological predisposition is compounded by the supply of super convenient, delicious, processed food, which lies at the root of our problem. As weight-inducing meals began to hit store shelves, technology simultaneously made our lifestyles increasingly more sedentary. The growing problem of obesity brings a host of related health issues, such as diabetes, heart disease, high blood pressure, stroke, gout, and various cancers.

While fat-shaming is undeniably wrong, the stigma associated with being obese poses a tough challenge to change and contributes to widespread unhappiness. It’s against this backdrop that drugs like Semaglutide and its counterparts are emerging as potentially effective solutions. These treatments promise to make a significant difference in addressing obesity.

So, how do these drugs work? The once-a-week injection serves as an appetite suppressant by mimicking the hormone known as Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1). GLP-1 is released after eating to signal feelings of fullness and satisfaction; Semaglutide mimics this response, helping individuals feel satiated and thereby reducing overeating. It also suppresses our biological, instinctive urge to eat, something even the most determined dieters struggle to control.

The effectiveness of Semaglutide was first observed among diabetes patients using Ozempic, a medication that contains the same active ingredient. Dr. Jennifer Levine, a New York-based surgeon, explains, “Ozempic, which contains Semaglutide, is used to treat diabetes and has been very effective for weight loss. It works by causing the pancreas to secrete more insulin and decreases the amount of glucagon produced by the liver, which suppresses appetite and slows down gastric motility, so you feel full for longer.”

International banking giant UBS predicts that Semaglutide could become the biggest drug in history. Meanwhile, Jefferies, a US investment bank, estimates that by 2031, the market for these drugs could exceed US$150 billion, a figure on par with all cancer drugs combined. Here in New Zealand, we’re not immune to the tightening of our clothes; in 2021, around 34.3 percent of New Zealanders were classified as obese, our highest statistic ever.

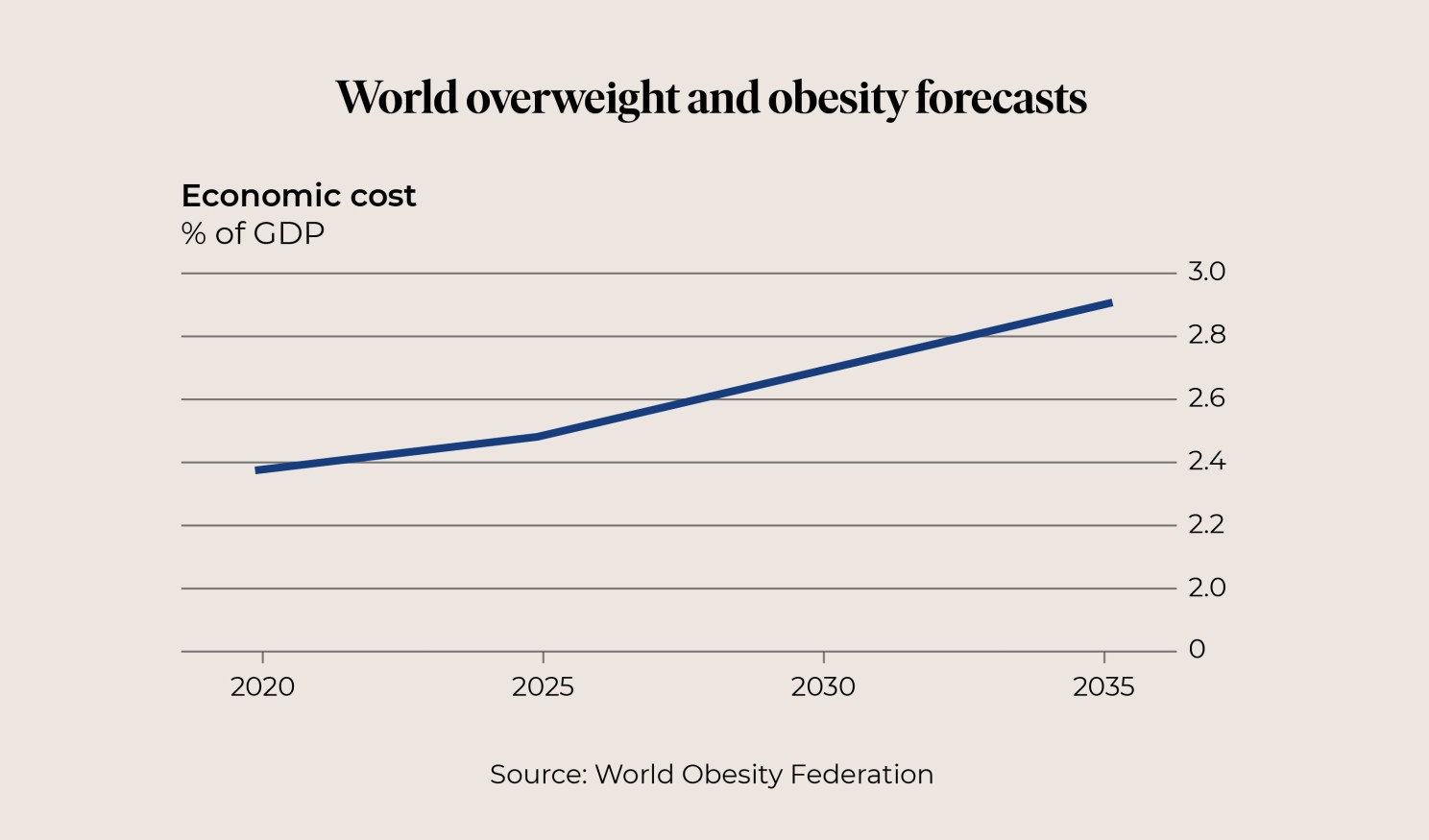

A recent report indicates the annual cost of humanity's increasing waistlines could reach $4 trillion by 2035. This staggering amount represents nearly 3% of global GDP, factoring in healthcare spending and productivity losses due to illness and premature deaths—an impact equivalent to another COVID-19 pandemic every year.

Given these considerations, it seems common sense that any treatment capable of reversing these troubling statistics and enhancing the health of billions should be seriously evaluated. The FDA in the United States and the NHS in the United Kingdom have already approved this new obesity therapy, although in the UK, it is currently restricted to targeted populations.

As nations confront their escalating healthcare costs, the long-term cost-benefit analysis of obesity-reducing drugs is likely to receive serious attention from policymakers. Savings accrued from reduced obesity-related health problems could be redirected to support other essential healthcare needs, such as hiring more well-paid nurses, enhancing ambulance services, expanding hospital capacity, and funding new lifesaving cancer treatments.

However, with any new medication comes a degree of risk. Like most drugs, Semaglutide is not without side effects, which can include nausea, stomach pain, vomiting, and diarrhea. Additionally, it appears to increase the risk of pancreatitis, a rare but serious condition, and there are still unanswered questions regarding its effects during pregnancy or shortly preceding it.

So, who will have access to this weight-loss solution, and at what cost? Unfunded, it is certainly not cheap. Once prescribed, it is designed to be a lifelong treatment, similar to blood pressure medications. In Britain, where the NHS has just approved its use, the price is around NZ$150 for four injections when obtained through Boot’s online doctor services. In contrast, reports suggest that monthly costs in the USA may reach as high as $1,400.

Notably, there are accounts that high-profile individuals like Elon Musk advocate for Semaglutide's effectiveness. For those with the financial means, including Hollywood stars and a growing list of influencers promoting it on TikTok, cost is less of a concern.

For me, the emergence of Semaglutide represents a significant advancement. It reframes obesity as a legitimate health condition rather than simply a consequence of poor self-control—an issue that can be treated with a therapy that promises benefits for both individuals and communities.

If obesity rates continue to rise unchecked, millions of people worldwide may face debilitating health issues that could significantly shorten their lives. Given these dire projections, it seems only practical to pursue viable treatments that can mitigate this growing health crisis.

In many relatively high-income countries, such as New Zealand, obesity rates are higher among individuals with low incomes. Additionally, these rates are elevated within our Pasifika and Māori communities.

It will be interesting to observe how the debate unfolds in New Zealand, where Pharmac is responsible for wisely managing the nation’s pharmaceutical budget to promote well-being and achieve equitable health outcomes.

As always, I would love to hear your thoughts or observations on this important issue. Please share your comments on the post below or feel free to email me at ceo@unimed.co.nz.

Nga mihi,

Louise.